The Federal Aviation Administration’s headquarters is at 800 Independence Avenue SW in Washington, D.C., directly across the street from the Smithsonian’s Hirschhorn Museum and the Air and Space Museum.

A marker on the sidewalk out front, erected in January 2017, explains what used to be there:

“An infamous slave pen, owned by W.H. Williams ...

A seemingly innocuous yellow house, set back from the street in a grove of trees, concealed from view a brick-walled yard, in which enslaved persons were held, awaiting transport to southern markets.

It was one of the most lucrative of the slave pens operating in Washington, DC in the years before the Civil War.”

The marker almost certainly would not be there if it not for the experience of one of the many people who were held in chains there. It continues:

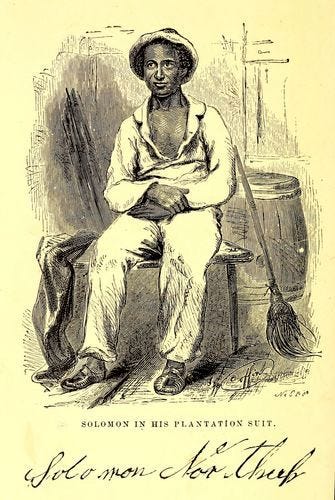

In 1841, Solomon Northup, a free Black man and professional musician, was drugged, kidnapped, and sold as a slave while visiting Washington, DC ...

Eventually, Northup regained his freedom and documented the experience in his book, Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup (1853).

Northup was 33 years old at the time that he was tricked, kidnapped, and sold into slavery.

He’d lived his entire life up until then in upstate New York, where he had a wife, Anne, and three children: Elizabeth, Margaret, and Alonzo. Northup made his living as a carpenter and a violinist, skilled enough that local hotels hired him for their dances. He owned property. He voted.

In March 1841, two men he met in Saratoga Springs offered him work playing the fiddle for their traveling circus. As Northup later wrote, they paid him well and worked to ensure he obtained papers showing his free status.

But then, he was drugged — in his book, Northup seems to be unsure whether it was the two men who’d convinced him to head South who had done so, or someone else—but regardless, he lost consciousness and woke up in chains in a cell in the Williams Slave Pen.

His money and documents were gone, and he was beaten brutally for hours until he stopped insisting the he was a free person from New York. Within days, Solomon Northup became “Platt”—a runaway slave from Georgia.

He was shipped to New Orleans, where he was auctioned for $1,000. What followed were twelve years on Louisiana cotton and sugar plantations.

Twelve years of whippings, forced labor, and the constant threat of violence.

Twelve years watching other enslaved people ripped from their families, children sold away from mothers, human beings treated as property.

Twelve years wondering if somewhere in New York, his wife and children had any idea if he was alive or dead.

Nearly 12 years, before deliverance came, largely in the form of a Canadian carpenter named Samuel Bass, who abhorred slavery, and in whom Northup confided.

Bass sent letters to Northup’s family and friends back home in Saratoga Springs; some of those friends mobilized support among prominent citizens and convinced New York Governor Washington Hunt to appoint a white friend of Northup’s with the same last name—Henry Northup—as an official state agent, and send him to Louisiana under an 1840 law designed to rescue kidnapped citizens.

Armed with affidavits and court documents, and accompanied by the local sheriff, Henry Northup located Solomon Northup and reached the plantation where he was held by a brutal plantation owner called Edwin Epps, on January 3, 1853.

The next day as Solomon Northup wrote:

Tuesday, the fourth of January, Epps and his counsel, the Hon. H. Taylor, [Henry] Northup, Waddill, the Judge and sheriff of Avoyelles, and myself, met in a room in the village of Marksville.

Mr. Northup stated the facts in regard to me, and presented his commission, and the affidavits accompanying it. The sheriff described the scene in the cotton field. I was also interrogated at great length.

Finally, Mr. Taylor assured his client that he was satisfied, and that litigation would not only be expensive, but utterly useless.

In accordance with his advice, a paper was drawn up and signed by the proper parties, wherein Epps acknowledged he was satisfied of my right to freedom, and formally surrendered me to the authorities of New-York.

Three weeks later, on January 21, Solomon reunited with his family. His daughters had married. He’d missed years of their lives.

They had known he had been enslaved, but had no idea where in the South he had been taken, or what name he was living under. One of his sons had spent the entire 12 years obsessed with the idea of earning and saving enough money to travel the South, find his father, and buy his freedom.

Within months, working with editor David Wilson, Northup published his memoir. Twelve Years a Slave was a bestseller, with 30,000 copies in three years.

More importantly, it became proof: a firsthand account by a man who’d lived as both free citizen and enslaved person, who could describe the mechanics of plantation slavery with the authority of lived experience.

I’ve pulled punches in describing what slavery was like for Solomon Northup and others above; frankly it’s very hard for me even to conceive what it was like.

But, the book did no such thing. It named names, places, dates, and offered evidence.

It galvanized Northern readers who might otherwise have remained indifferent—much like Uncle Tom’s Cabin, only presented as a true story.

Northup became an active abolitionist, giving speeches throughout the Northeast, staging plays based on his story, and it seems clear, helping others escape via the Underground Railroad.

Within five years afterward, however, Solomon Northup disappeared from the historical record. How he died, where he died—nobody knows.

His book disappeared too.

After several 19th-century printings, *Twelve Years a Slave* was forgotten for nearly 100 years, until 1968, when historians Sue Eakin and Joseph Logsdon discovered it and published an annotated edition.

In 2013, director Steve McQueen adapted the book into a film that won the Academy Award for Best Picture.

It’s hard to think of anything “optimistic” about Solomon Northup’s story, except how it ended, literally 172 years ago yesterday.

But had he not gone through his ordeal, people might not have known, and history might been a little bit different.

7 optimistic moments from history this week

Sunday, January 4: “Let us reaffirm our commitment to work together for an inclusive and equitable world, where the rights of people with disabilities are fully realized.” — UN Secretary-General António Guterres, in an official message for the first World Braille Day, this day in 2019.

Monday, January 5: “Now, what you hear is not a test, I’m rappin’ to the beat ...” opening line to “Rapper’s Delight” by the Sugarhill Gang, which broke the Billboard Hot 100 Top 40 on January 5, 1980, reaching #36, the first rap song to do so.

Tuesday, January 6: “A patient waiter is no loser.” — Samuel Morse, in one of the first demonstrated telegraph messages, on this day in 1838. The message was transmitted over two miles of wire in Morristown, N.J.

Wednesday, January 7: “Hello? Is that Mr. Gifford? Well, good morning, Sir Evelyn.” — First lines from the first transatlantic telephone call (recorded and preserved at the Library of Congress), on this day in 1927 between the President of America’s AT&T company, Walter S. Gifford, and the head of the British General Post Office, Sir Evelyn P. Murray.

Thursday, January 8: “Let us commemorate it as an event that gives us increased power as a nation ...”—a toast from President Andrew Jackson this day in 1835, marking the only time in U.S. history that the national debt has been reduced to zero.

Friday, January 9: “Every once in a while, a revolutionary product comes along that changes everything.” — Steve Jobs, this day in 2007 introducing the iPhone.

Saturday, January 10: “The excitement of the public to get places, and the running about of officials ... no doubt took up more than half the time which will be occupied by the stoppage of a train at each station on ordinary occasions.” — from a contemporary article in The Guardian, describing the opening of the London Underground on this day in 1863.

Thanks for another engaging essay! The cruelty some people are capable of inflicting on other human beings never ceases to amaze me.

“It's an old and obvious pattern. An unpopular president - failing on the economy and losing his grip on power at home - decides to launch a war for regime change abroad.

The American people don’t want to “run” a foreign country while our leaders fail to improve life in this one.”

— Pete Buttugieg

What have we learned from history? May not be slaves any longer, but racism and discrimination are alive and well. The colour of your skin or what religion you follow does not make you a lesser person. I think that racism to some degree is just human nature, we all like to be with our own tribe. But that doesn’t lessen the value of other tribes.

pretty sure Trump is going to start another world war.