A lamb surrounded by wolves

Extracts From My Diary and My Experiences, While Boarding With Jefferson Davis In Three of His Notorious Hotels

In 1901, a man named William Crossley, who was then in his early 60s and who had a dry wit and a way with words, addressed the Rhode Island Soldiers and Sailors Historical Society.

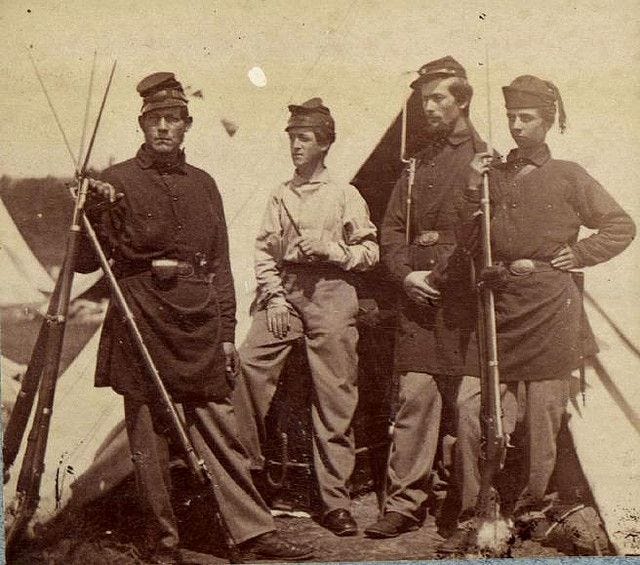

The topic: his experience as a Union soldier during the Civil War who had served only 46 days before being wounded and captured by the Confederate army.

Crossley then spent 300 days as a prisoner before he was exchanged. (Then, he went back into combat, fighting in seven other battles between 1862 and 1864.)

Still later, Crossley turned his talk—which was based on his war diary—into a short book. Google helpfully scanned it more than 100 years later.

The title gives you a sense of Crossley’s sense of humor: Extracts From My Diary and My Experiences, While Boarding With Jefferson Davis In Three of His Notorious Hotels.

The Civil War started in April 1861. Crossley joined the 2nd Rhode Island Infantry Volunteers in May, was mustered into federal service in June, and was promoted to sergeant and then fought at the first Battle of Bull Run on July 21—becoming a “guest of the Confederacy” literally the following day.

His time in captivity was tough, but if you’ve heard of the notorious Andersonville camp, it wasn’t quite that bad. For one thing, he was a POW two years before that camp opened, and for another he was eventually paroled—which wasn’t really an option later.

(When the Union formed Black units, the Confederates refused to trade Black soldiers for White ones. So soldiers who were captured later were mostly stuck in captivity until the end of the war.)

Crossley writes that he was 21 when he was captured, but he explains in the diary-turned-speech-turned-book that he quickly learned to tell the guards he was just 17, so he’d get better treatment. Other excerpts:

Monday, July 22, 1861.

“Well, here I am, a prisoner of war, a lamb surrounded by wolves, just because I obeyed orders, went into a fight, and, by Queensbury Rules, was punctured below the belt [by which Crossley meant he was shot in his thigh]. So much for trying to be good.”

For the next few weeks, he records two things: what he ate for dinner, and the names of people who died. Examples…

July 27th.

“No bread to-day, only gruel. McCann, of Newport, died.”

And…

July 28th.

Major Ballou died this p.m. Gruel for supper, with a fierce tempest.

Here’s one more, since today would be the anniversary, August 26:

“Light breakfast, no dinner and small supper. The front of my stomach and my spinal column seem to be about three-quarters of an inch apart now.”

Eventually, Crossley and his fellow soldiers were carted all over the South by their captors. A dark sarcasm develops—describing a bleak existence, but with enough wry humor to make the reader forget just how bleak the surroundings actually are.

“Next morning, taken upstairs, and ‘bless my stars,’ put on cots, and given bread and coffee for breakfast.

What was the coffee made of, do you ask? I don’t know, and, as you didn’t have to drink it, it need not concern you; and we had soup for dinner, and it’s none of your affairs what that was made of either.”

Finally, this passage—which comes from just after Crossley’s release, when he and his surviving fellow soldiers have been turned over to the Union Army in North Carolina, and are beginning their way home—and which was excerpted briefly in a New York Times article about soldiers and coffee a few years ago, and which led me to the diary to begin with:

“Coffee, soup and crackers for supper. Oh! but wasn’t that coffee rich?

And can I ever forgive those Confederate thieves for robbing me of so many precious doses; just think of it, in three hundred days there was lost to me, forever, so many hundred pots of good old Government Java. …

Though I have been taught to forgive, seventy times seven is a good many, and it’s a long way back to last July. …”

When I first shared this story more than two years ago, I wasn’t able to find out anything about what happened to Crossley after his 1901 speech. But, a reader with an interest in genealogy came to the rescue with this summary:

Short version: William J. Crossley, who was born in Manchester, England, came to the United States as a child in 1842. After his Civil War service, he came home to Rhode Island, worked as a grocer, was married for 45 years and had five children.

In retirement, he and his wife moved from Rhode Island to Pasadena; after his first wife’s death, he remarried at age 73. Crossley died in 1929, at age 90. A pretty full life!

If you’re like me and you can get lost in this kind of obscure, old account, here’s a link to the whole thing (plus quite a few other accounts).

(Reminder, while we’re running on “low power mode,” we’ll be skipping the “7 other things” we normally run. But I invite you to share links to things you think your fellow readers would appreciate or enjoy in the comments.)

A lesson in survival while keeping your sanity, or at least your wit intact.

Hi Bill: I miss the "Five other things to know/read"! Will those links return?