Franklin McCain was 6’2” and weighed over 200 pounds.

As a Black freshman at North Carolina A&T in the fall of 1959, he towered over most of his classmates. Despite his intimidating build, he was quiet—no athlete, no campus celebrity, just a kid who preferred the close companionship of friends.

Even as a child, however, McCain had tested the absurdity of segregation in his own small way.

He’d drink from both the “white” and “colored” water fountains to see if the taste was different. By the time he got to college, he later said, “I was angry with a system that led me on and betrayed me, and destroyed most of my faith in a lot of humankind.”

McCain lived in a dormitory with David Richmond and in the same building as Ezell Blair Jr. and Joseph McNeil, and the four Black students became close friends.

They’d gather in someone’s dorm room for conversations about racial inequality that would stretch so long they’d fall asleep right where they sat. They talked about Gandhi’s nonviolent resistance, about the Freedom Rides, about the murder of Emmett Till.

They read about the sit-ins that had already happened in other cities—Wichita in 1958, Oklahoma City that same year—protests that had worked.

“We finally felt hypocritical,” McCain said, for doing nothing.

They decided to sit at the whites-only lunch counter at Woolworth’s in downtown Greensboro. It was McCain who gave the final call when his friends began to get cold feet.

Quiet McCain, who is remembered for asking: “Are you guys chicken or not?”

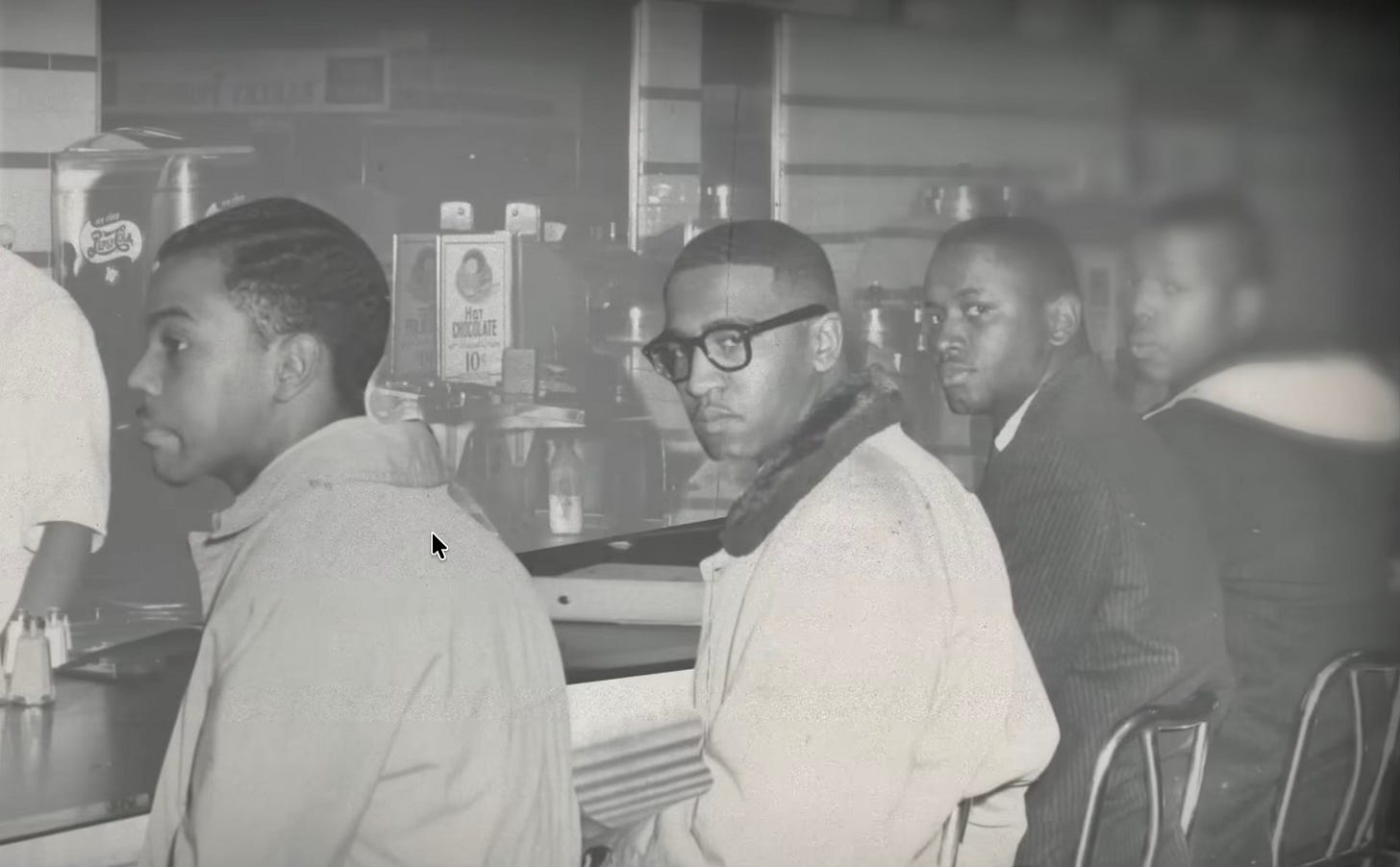

On the late afternoon of Monday, February 1, 1960, the four young men walked into the F.W. Woolworth at 132 South Elm Street. They bought toothpaste and other small items from a non-segregated counter, saving their receipts.

Then, dressed in their Sunday best, they sat down at the 66-seat L-shaped lunch counter and asked for coffee and donuts.

“We don’t serve Negroes here,” a white waitress told them.

Blair pointed out that he’d just been served two feet away. The waitress replied, “Negroes eat at the other end.”

They didn’t move.

A white police officer arrived with his billy club drawn and asked them to leave. They stayed.

The store manager asked them to leave. They stayed.

An older Black woman who worked behind the counter called them “stupid, ignorant, rabble-rousers, troublemakers.” They stayed.

McCain compared himself and the others to “Mack trucks” because there was no way anyone could move them from their seats. The longer they sat, the more McCain realized that no one was stopping them.

He thought: “Maybe they can’t do anything to us; maybe we can keep it up.”

The store closed at 5:30 p.m. They left.

None of them had been arrested. The police had declared they could do nothing because the four men were paying customers who had not taken any provocative actions. But local businessman Ralph Johns, who had helped the students plan the protest, had already alerted the media.

A photo of the Greensboro Four appeared in local newspapers.

The next day, they returned with more than 20 other students. By February 3, more than 60 students joined them, including women from Bennett College and students from Dudley High School.

By February 5, some 300 people had packed into Woolworth’s, filling virtually every seat at the lunch counter and spilling onto the sidewalk outside.

At one point, an older white woman who walked up behind him as he sat at the counter. She whispered in a calm voice: “Boys, I’m so proud of you.”

(McCain would later say: “What I learned from that little incident was don’t you ever, ever stereotype anybody in this life until you at least experience them and have the opportunity to talk to them.”)

Within a week, sit-ins had spread to 15 cities in five states. Within two months, 54 cities in nine states had protests of their own.

More than 70,000 people eventually participated in the sit-in movement.

Historian Howard Zinn wrote, “It is hard to overestimate the electrical effect of that first sit-in in Greensboro.” For the first time in American history, he argued, “a major social movement, shaking the nation to its bones, is being led by youngsters.”

The Greensboro Woolworth’s lunch counter quietly desegregated on July 25, 1960—six months after that first afternoon.

The first people served were four Black employees of the store: Geneva Tisdale, Susie Morrison, Anetha Jones, and Charles Best.

McCain graduated from A&T in 1964 with degrees in chemistry and biology. He married, had three sons, and spent more than three decades working as a chemist in Charlotte. Throughout his life, he remained proud of what happened that day. He said he never felt more powerful or confident than while protesting segregation.

“I felt clean,” he remembered about sitting at that lunch counter. “I had gained my manhood by that simple act.”

A portion of that Woolworth’s lunch counter—four stools where McCain and his friends sat—is now preserved at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

The building itself has become the International Civil Rights Center and Museum. On the North Carolina A&T campus, a statue honors the four friends.

It’s called “February One.”

McCain died in 2014 at age 73, a chemist from Charlotte who once sat down in a five-and-dime store and helped change America.

7 optimistic moments from history this week

Sunday, February 1: “The Grand Central Terminal is not only a station, it is a monument, a civic center, or, if one will, a city.”—The New York Times on this day in 1913 when the world’s largest train station opened in New York City after a decade of construction.

Monday, February 2: “The civilisation of a people can be measured by their domestic and sanitary appliances.”—George Jennings. On this day in 1852, the first public flushing toilets opened at 95 Fleet Street in London, following the success of Jennings’ “Monkey Closets” at the 1851 Great Exhibition where over 800,000 visitors paid a penny to use them—coining the phrase “spend a penny.”

Tuesday, February 3: “I laid violent hands upon it without asking permission of the proprietor’s remains,” Samuel Clemens later explained about adopting the pen name “Mark Twain” on this day in 1863 for his first signed article in the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise. The riverboat term meaning “two fathoms deep” became one of American literature’s most famous pseudonyms.

Wednesday, February 4: “I can do it better than they can, and I can do it in a week,”—Mark Zuckerberg, before launching Facebook on this day in 2004. Within 24 hours, 1,200-1,500 Harvard students had signed up for what would become the world’s largest social network.

Thursday, February 5: “Miles and miles and miles.”—astronaut Alan Shepard, after hitting a golf ball on the Moon on this day in 1971 during the Apollo 14 mission. Later analysis revealed the shot traveled 40 yards—still an impressive feat for a one-handed swing in a bulky spacesuit.

Friday, February 6: “The High and Mighty Princess Elizabeth Alexandra Mary is now, by the death of our late Sovereign of happy memory, become Queen Elizabeth the Second.”—proclamation of the Accession Council on this day in 1952 after King George VI died in his sleep at Sandringham. Princess Elizabeth, just 25, learned of her father’s death while on safari in Kenya and immediately became Queen.

Saturday, February 7: “This Treaty marks a new stage in the process of creating an ever closer union among the peoples of Europe.”—Proclamation upon the signing of the the Maastricht Treaty this day in 1992, which established the European Union and laid the groundwork for the euro.

Thanks Bill, history is so important. In an age of fast food and fast truth History rightly told unmasks our path. My aunt is 103 1/2 years of age. In her lifetime we went from ice boxes and shared telephones (in Toronto), horses pulling Dad's cookies delivery vans to the moon. We need to gather the history, share it and let it shape the days ahead.

Love the story of Franklin McCain ! Thank you for posting it !