Big Optimism: 'There is your flag'

A Canadian story today. I'll be interested to know if our Canadian readers already know it?

George Stanley was just trying to help a friend when he pointed at the flagpole.

It was March 1964, and the two men were walking across the parade ground at the Royal Military College in Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Stanley was Dean of Arts there—a military historian who’d spent his career thinking about what held countries together and what tore them apart.

His friend, John Matheson, was a Liberal member of parliament with a problem. Canada was tearing itself apart over a flag.

Prime Minister Lester Pearson wanted a new flag—something distinctly Canadian, not the Red Ensign with its Union Jack.

But veterans who had fought under that flag felt betrayed. The Royal Canadian Legion had erupted at Pearson’s speech, and Opposition Leader John Diefenbaker thundered about abandoning Canada’s British heritage.

A parliamentary committee asked for ideas, and was now drowning in submissions: thousands of flags, with beavers, multiple maple leaves, the fleur-de-lis. Nothing was working.

Matheson walked with difficulty; a veteran himself, he’d been wounded at the Moro River during the war. As they crossed the parade ground, Stanley gestured toward the Mackenzie Building, where the college flag snapped in the wind.

Red-white-red. Two red bars flanking a white square with the college crest.

“There is your flag,” Stanley said.

It was almost offhand, but as a soldier and an historian, Stanley had been thinking about symbols his whole life.

Did you get the memo?

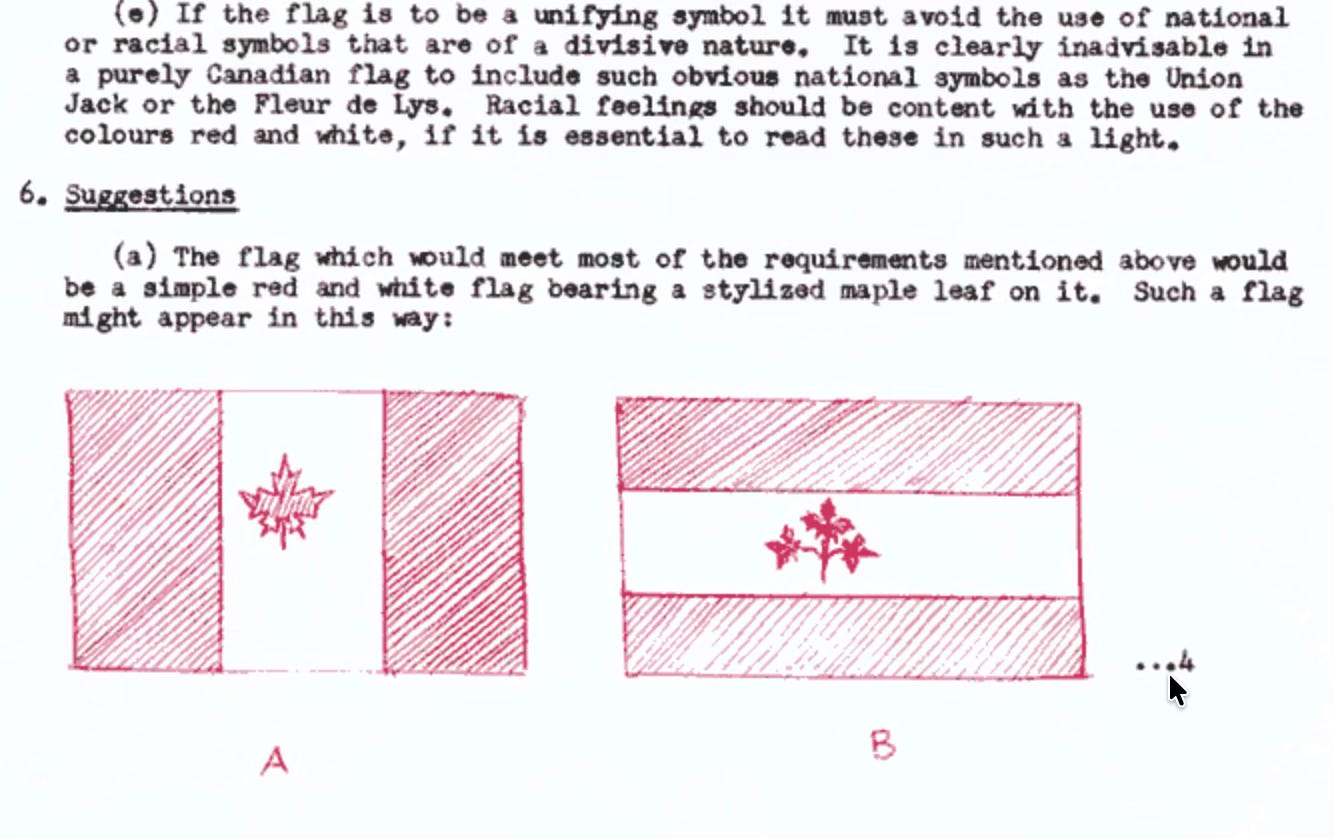

Two weeks later, March 23, 1964, Stanley sat down and wrote a four-page memo to Matheson explaining his ideas for a new Canadian flag. (Full memo here.)

The greatest symbols were simple, he wrote, and no flag could represent everything—that was everyone’s mistake.

“If the flag is to be a unifying symbol,” he wrote, “it must avoid the use of national or racial symbols that are of a divisive nature.”

So, it had to skip the Union Jack and the fleur-de-lis. It had to be so simple a child could draw it—highly distinctive and recognizable from a distance.

The RMC flag wasn’t the answer, but it was close, he wrote. Red and white had been Canada’s colors since 1921. What if you stripped away everything else?

At the bottom of page three, he sketched his design—a doodle, really. A single maple leaf, centered on white, flanked by two red bars.

The Great Flag Debate

The memo made its way to the committee room, where Stanley’s sketch was placed among hundreds of professionally rendered designs. The committee remained deadlocked through spring, summer, and into fall.

Prime Minister Pearson favored a different design—the “Pearson Pennant” with three maple leaves and blue bars, but on October 22, the committee chose Stanley’s design.

A graphic artist named Jacques Saint-Cyr had refined the maple leaf to eleven points for better visibility. Another designer adjusted the proportions. But the concept was Stanley’s.

Then came the “Great Flag Debate.” The House of Commons still had to vote, and the fight raged for six more weeks. Diefenbaker fought until the end, urging his party to vote for the red-and-white maple leaf design on the assumption that Liberals would vote for Pearson’s preferred pennant, and continue the stalemate.

But Liberals switched their vote, and on December 15 at 2 a.m., Parliament invoked closure. The vote for the new Maple Leaf flag was 163 to 78.

Stanley had long since left the capital. The official flag-raising ceremony was set for February 15, 1965, and Stanley received death threats for having come up with design, warning he’d be shot if he showed up.

But Stanley had been shot at before. So, he wore his colorful Hudson’s Bay coat to the ceremony anyway and watched as his design rose on the flagpole on Parliament Hill at noon in front of thousands of Canadians in the cold.

The newspapers credited Pearson, or Matheson, or called it a committee effort. And over time, Stanley’s role was nearly forgotten.

Stanley went on to become Lieutenant Governor of New Brunswick and received the Order of Canada. He died in 2002 at 95.

But he’s the one who came up with the Canadian answer: subtraction instead of addition. A country as divided as Canada needed a symbol so simple it couldn’t belong to any faction.

---

P.S. — I thought as I was writing this: Was Stanley related to Lord Stanley, the British aristocrat who donated the Stanley Cup in 1892?

Nope. Different families, different centuries, same last name.

It’s a bit of a coincidence though that Canada’s two most famous Stanleys both gave the country its two most famous symbols.

7 optimistic moments from history this week

Sunday, February 15: “I don’t think my name is likely to be worth much in the bear business, but you’re welcome to use it.” — President Theodore Roosevelt, reply to Morris Michtom, on this day in 1903, granting permission to name a stuffed toy “Teddy’s Bear.”

Monday, February 16: “The first man-made organic textile fabric prepared entirely from new materials from the mineral kingdom.” — DuPont’s announcement in 1938 describing the invention of nylon, on this day in 1937.

Tuesday, February 17: “Hello! This is New York calling.” — The opening words of Voice of America’s first Russian-language broadcast, this day in 1947. Programming included news, human-interest stories, and music—especially jazz.

Wednesday, February 18: “Dr. Slipher, I have found your Planet X.” — Clyde Tombaugh, a 24-year-old self-taught astronomer from Kansas, to Lowell Observatory Director V.M. Slipher, on this day in 1930, after discovering Pluto.

Thursday, February 19: “The phonograph will undoubtedly be liberally devoted to music.” — Thomas Edison, predicting the future of his invention, on this day in 1878, when he received U.S. Patent No. 200,521 for the phonograph. Edison developed the device while working on telegraph and telephone technology.

Friday, February 20: “Godspeed, John Glenn.” — Astronaut Scott Carpenter’s farewell to John Glenn at launch, on this day in 1962, as Glenn became the first American to orbit Earth.

Saturday, February 21: “An earthquake may shake its foundations...but the character which it commemorates and illustrates is secure.” — Robert Winthrop’s dedication speech for the Washington Monument, on this day in 1885. President Chester Arthur presided over the ceremony. The monument opened to the public in 1888 after elevators were installed.

Quite the home run Bill. Great story on Family Day in Canada. Now I gotta go look that up! Happy Family or Heritage Day Canadians! And Happy Flag Day yesterday!

Sorry our president has been treating you so poorly.

Great story thanks Bill, I am a Canadian that did not know of another Stanley. Appreciate a story like this on our Federal holiday, Family Day, Oh Canada

Keep up the great stories and newsletters Bill!